LIGHT BENT BACKWARD, WAITING TO BE FORGOTTEN

curated by Anzhelika Palyvoda

29.05. - 11.06.2025

arka arka

Stammgasse 11, 1030 Vienna

Falter

saliva.live

part of Independent Space Index Vienna

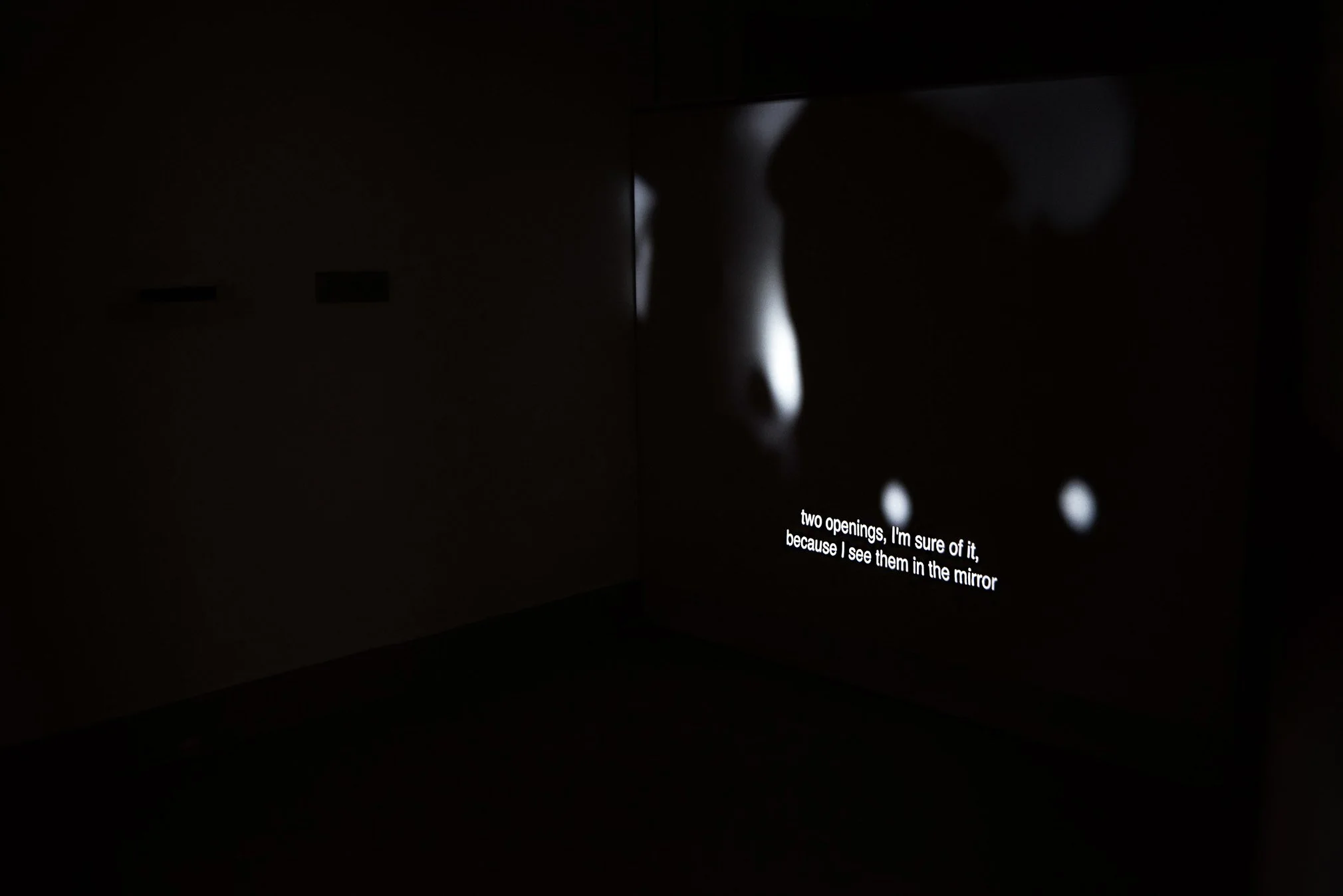

“The exhibition brings together three artistic practices in which light — traditionally a symbol of visibility, knowledge, and truth — no longer moves forward. It refuses to be guiding, all-penetrating. Instead, it turns toward oblivion, distortion, and transformation. Light no longer illuminates but recedes — like memory, like voice, like a trace dissolving into matter. The deviation backward becomes a gesture pointing to resistance against the linearity of time, or to something that once moved forward but now unexpectedly retreats. This is exhibition about what becomes invisible, elusive, unfixable — about materials susceptible to decay. About structures that seem clear at first glance but conceal duality — violence and ideology. In the practice of Nabil Aniss, light is less a visual phenomenon and more an inner energy that arises through sound, movement, trance, and self-harm. Aniss engages with the history of oppression and mysticism as acts of liberation. In his new work Structures and Positions, Aniss refers to Michel Foucault’s essay The Utopian Body, in which the body is described as elusive, both real and impossible. In this film, the body becomes an "in-between" space, oscillating between visibility and disappearance, between social control and emancipation. Light here serves as a metaphor for a utopian gesture: a departure from fixed bodily identities and the unveiling of spaces of freedom hidden within ritual. In his films, bodies become sources of light that, however, deviate backwards — inward, toward their origins. Céline Struger works within a space where the organic and the artificial, the material and the fluid, interact in an eternal cycle of transformations. Her sculptures and installations are traces of processes that have already begun and are yet to be completed. Water — her primary material — flows through forms, changes them, and destroys them. It interacts with rust, tannins, and pigments, creating painterly traces of time, erosion, and entropy. In her practice, light is not an illuminating spotlight but a reflection — fleeting and temporary. Light may vanish into rust, dissolve in water, or be absorbed by porous surfaces. Here, light is decay. It deviates backwards, becoming a material trace of a lost presence. The space Struger creates is one where the sacred collides with the abandoned. In her practice, Sofiia Yesakova uses visual strategies that deliberately conceal emotional content within strict minimalist forms, prompting viewers to search for and carefully consider hidden meanings. Her works point to how a "pure" visual language can mask the violence of systems and ideologies. Yet within these schematics, there is a disruption. The lines are too thin, the images too fragile, the materials too alive — as if living imagery interrupts and destabilizes the rigid structures. Here, light is no longer absolute; it cracks, trembles, and loses focus. It deviates backwards — toward the pre-rational, the sacred, the iconological memory torn from its context and placed into a new space.In the works presented, the motif of bone decay (osteosarcoma) symbolizes the confrontation of physical form with human vulnerability. Across all three artistic positions, light is something that no longer strives toward the center. It slips away. It no longer points the way but turns toward the past, toward the body, toward ritual, toward material. It deviates backwards — to where memory is inseparable from forgetting, where form disintegrates in order to be reborn.”

Sofiia Yesakova

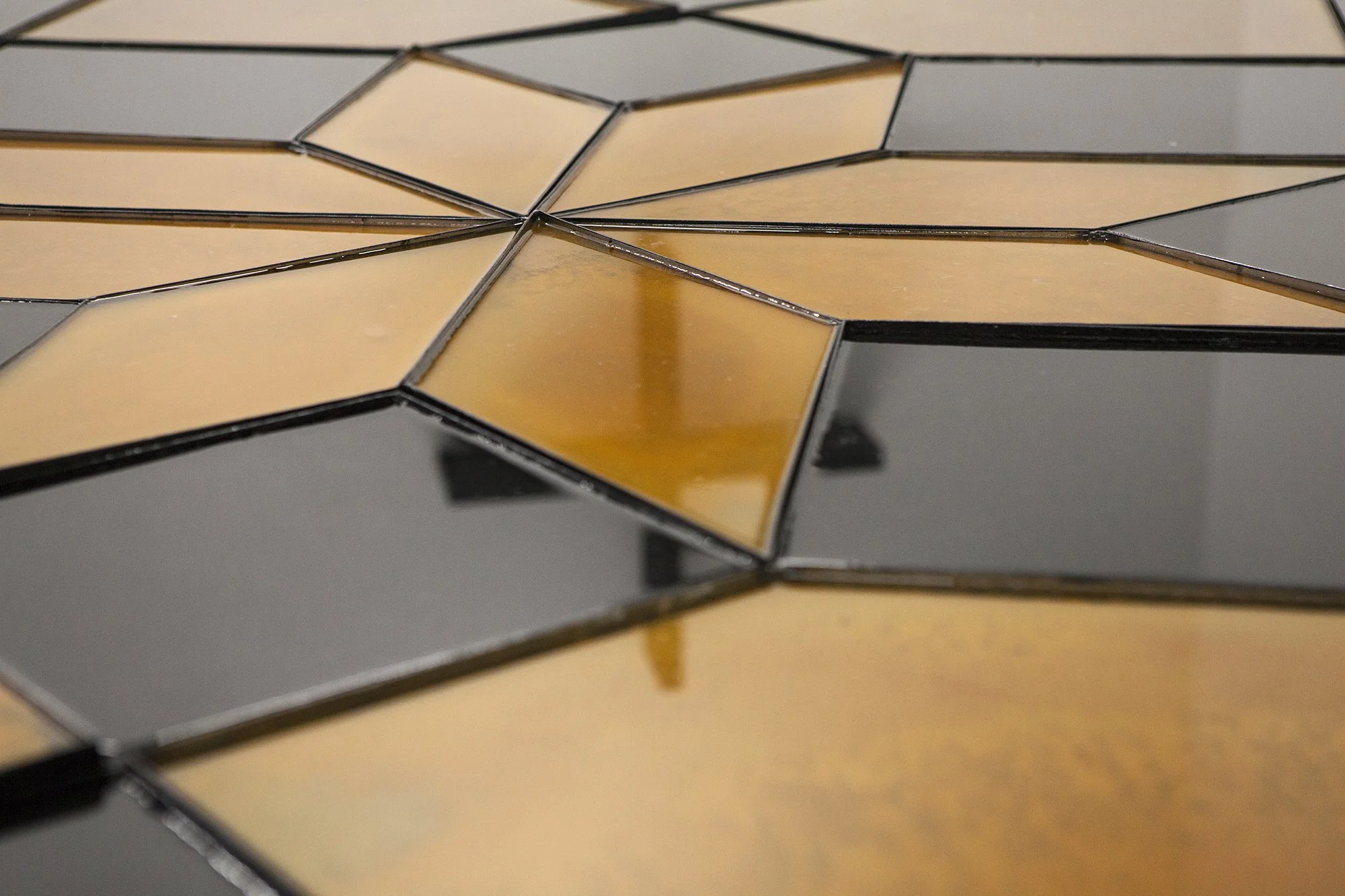

In The Flagellation of Christ by Piero della Francesca, divine suffering unfolds within the cool clarity of geometry. The floor tiles, with their measured recession in perspective, evoke not only spatial order but the ancient problem of squaring the circle — the impossible task of reconciling the perfect (the divine circle) with the earthly (the square). This mathematical allegory frames Christ’s flagellation as something more than brutality: it is proportioned, deliberate, and sacred. Writing in 1259, St. Bonaventure observed that “the mirror of visible things reflects the beauty of divine proportions,” just as pain reveals divine justice. The flagellants of the late Middle Ages enacted this belief physically, inscribing penance through the flesh in rhythm and repetition. Yet Georges Bataille introduces another argument: flagellation, for him, ruptures the self in contemplative excess, where meaning collapses. In Piero’s painting, the perfect form and sacred pain converge in an exquisite contradiction. This interplay of geometry and dissolution informs my own sculptural work: a shallow floor piece based directly on the tiled grid in Piero della Francesca’s painting. Each tile follows the square-circle motif, rendered in black varnish or raw steel. The black tiles absorb light like sealed voids; the untreated steel begins pale but rusts as it sits in water, slowly eroding into unpredictability. The initial clarity — a geometry of restraint — gives way to material excess. As in Piero’s scene, structure contains rupture: divine proportion is not immune to entropy, but frames it. Within this field, sacred pain, mystic excess, and the collapse of form coexist — not as opposites, but as antagonists of the same logic.

Céline Struger

Céline Struger, SERAPHIM, 41 x 35 x 212 cm, pewter/tin, 2023

Céline Struger, DIE VERHEISSUNG/THE FOREBODING, 1 x 212 x 212 cm, steel, water, rust, 2025

Céline Struger, MOTH AS IN MOTHER II, 280 x 20 x 13 cm, steel, stoneware, 2025

FC Janine Schranz

Sofiia Yesakova, Ugly scenes. Nuances 4.1., 100 × 100 × 5 cm (x2), black wood, linseed oil, beeswax, funeral ribbon, 2025

Sofiia Yesakova

Sofiia Yesakova, UGLY SCENES, NUANCES, 4.1., 100 × 100 × 5 cm, black wood, beeswax, funeral ribbon, 2025

Céline Struger, DIE VERHEISSUNG/THE FOREBODING, 1 x 212 x 212 cm, steel, water, rust, 2025

postcard depicting painting of Piero della Francesca

Sofiia Yesakova, UGLY SCENES, NUANCES 2.1., 15 x 5 x 3 cm, black wood, acrylic glass beeswax, 2025

Nabil Aniss, STRUCTURES AND POSITIONS. THE RELIGION OF SLAVES - 6/7 15 min, Belgium, 2023

Nabil Aniss

Sofiia Yesakova, Nabil Aniss

Céline Struger, Anzhelika Palyvoda, Sofiia Yesakova